Atmospheric methane, the second most important anthropogenic greenhouse gas after carbon dioxide, surged to record levels during the early 2020s, despite sharp drops in air pollution as human activity slowed during the COVID-19 pandemic. The paradox: the methane spike was not driven by human emissions but by a temporary collapse in the atmosphere's ability to break down the greenhouse gas.

Philippe Ciais from the Laboratoire des Sciences du Climat et de l'Environnement and his team, contributing to ESA's Climate Change Initiative RECCAP-2 project, used satellite-derived Earth observation data, atmospheric inversions and ground-based measurements to disentangle the processes underlying the surge – reduced atmospheric oxidising capacity and increased wetland emissions. COVID-19 lockdowns led to a sharp reduction in air pollutants that contribute to hydroxyl radical formation – the molecules that normally oxidise methane. With a lower than normal concentration of hydroxyl radicals available during 2020-2021, the atmosphere became temporarily less efficient at removing methane, allowing it to accumulate faster than usual. According to the new study, this reduced oxidising capacity accounted for approximately 80% of year-to-year methane variability.

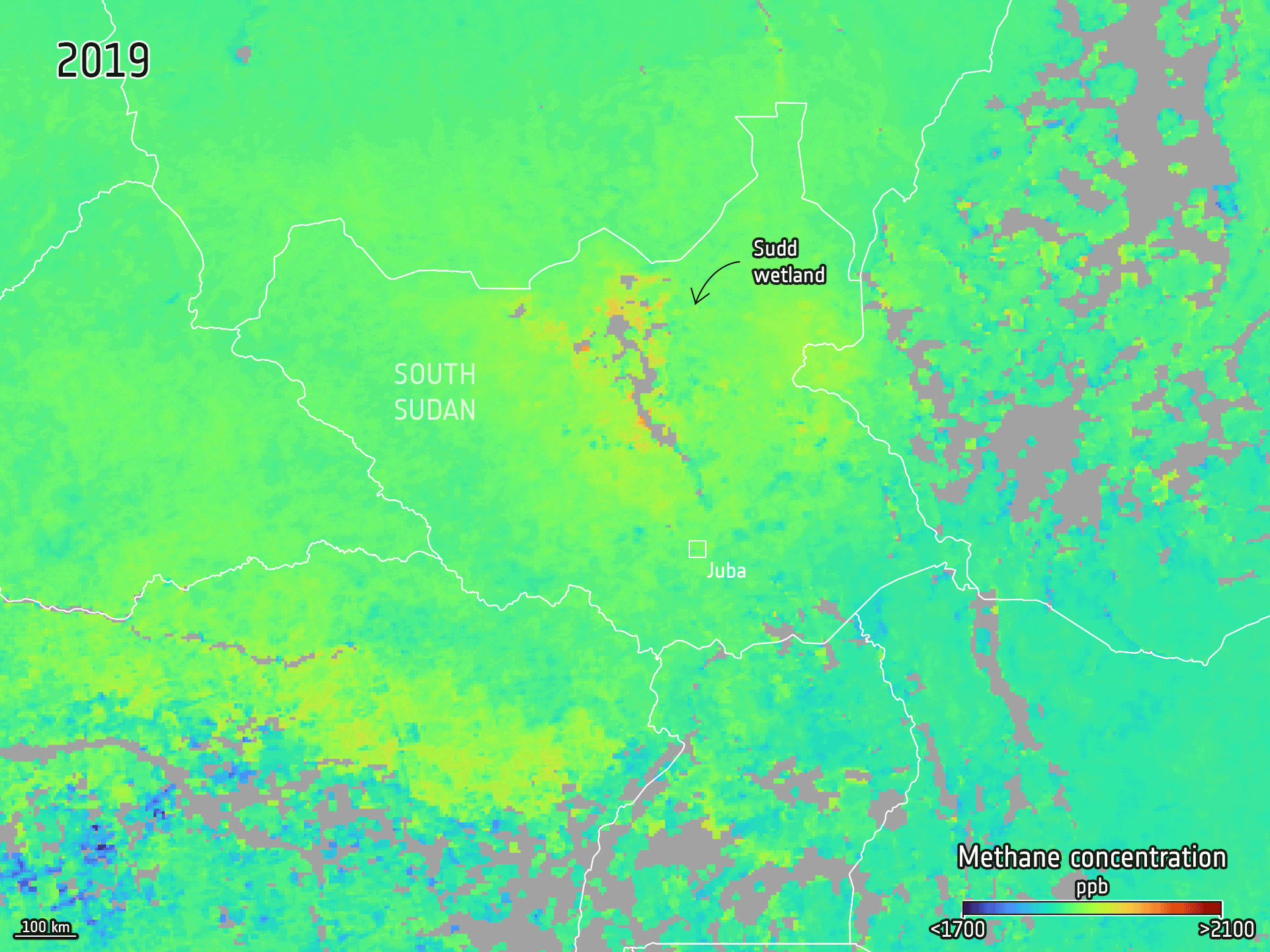

This change in atmospheric chemistry was amplified by increased emissions from northern tropical wetlands in Africa and Southeast Asia, where an extended La Niña period from June 2020 to June 2023 resulted in wetter conditions, which in turn expanded inundated areas and raised soil moisture, driving higher methane release from wetlands and inland waters.

Published in Science, the findings clarify the drivers of recent methane variability, reveal critical gaps in bottom-up wetland models, and provide updated methane budget data through 2023 to support Paris Agreement emissions monitoring and mitigation efforts.

Read the full article: ESA - The curious case of why methane spiked around Covid